Remote care services furnished via synchronous audio/visual technology or asynchronous “store and forward” technology, sometimes referred to as “telemedicine,” has seen increased use in recent years and even more so since the pandemic began. Telemedicine offers the dual advantage of at once expanding access to high quality care, and reducing the costs of furnishing and receiving care for providers and patients.

In recent times, telemedicine’s capabilities have been focused on furnishing care to and from brick and mortar facilities such as hospitals and clinics. This Article focuses on the significant benefits that may be available in connection with using telemedicine in the “prehospital” setting, when first responders are in the “field” working to furnish emergency services and to bring the patient to the appropriate care setting. In healthcare, the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) often consists of first responders (e.g. emergency medical technician, paramedic, nurse) providing basic and advanced life support in the uncontrolled “field” setting, including rural, suburban, urban, or remote care environments.

Telemedicine use by EMS agencies can be an excellent supplement to standard EMS offline and online medical control (rather than replace the application of written protocols or online medical control). An EMs agency’s written protocols should be applied prior to the initiation of any telemedicine application. The use of online medical direction remains an appropriate use of local physicians who are familiar with the EMS agencies, the providers of those agencies, as well as the receiving facilities. In situations where hospital based online medical control is challenging or limited (e.g. too busy working clinically to take EMS calls / consults), remote telemedicine use could be helpful.

County / State Line: Given the nature of EMS, it is possible for medical care to cross town, county, and even state lines. EMS systems that are considering integrating telemedicine capabilities should review any “crossing the border” issues that may arise when transporting a patient and crossing a border, including the scope of the telemedicine provider’s license. The EMS agency’s medical director should review the “what if” scenarios when leveraging telemedicine in the EMS environment.

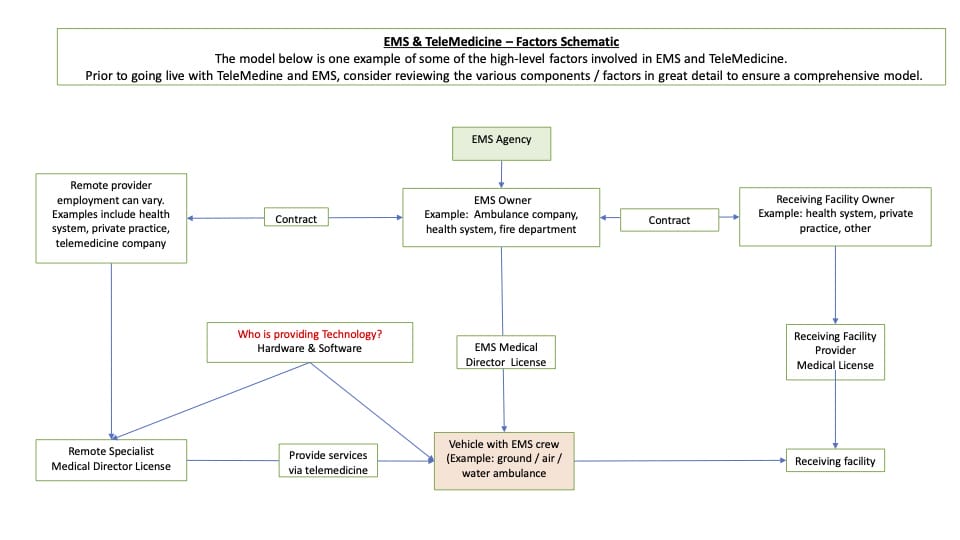

Remote telemedicine specialist / provider: Depending on the structure of the telemedicine system, the remote “telemedicine specialist” may be an employee or independent contractor of the EMS company. In some cases, it may be a provider who is outside the system and unfamiliar with the details and nuances of the EMS agencies and facilities in the area. This can work if the telemedicine application is truly being used for medical decisions rather than decisions specific to the EMS system. Such an application of telemedicine use for EMS allows providers who may not be board certified in EMS or Emergency Medicine (such as a neurologist or a dermatologist) to provide their expertise to EMS providers. Details such as employment status are important to identify for a variety of reasons including contractual terms, potential benefits, compensation rate, and what (if any) telemedicine hardware and/or software can be provided to the remote telemedicine specialist.

Physician License: In many situations, EMS staff function under a physician’s medical license. A medical physician must be licensed in the state where the physician practices medicine. Some states may have specific licenses that can be applied to telemedicine alone. When applying for an out of state license the EMS agency and out of state provider will need to keep in mind both the financial commitment as well as a time commitment as it can be costly and take several months to complete the process. Prior to implementing an EMS telemedicine program, the rules and regulations regarding the medical licensing and EMS crew oversight need to be clearly established and defined. Similar to the medical director, the remote specialist provider should be licensed in the state(s) where EMS may transport into.

Consent: Patients should agree and be formally consented to the application of a telemedicine consultation. Consent may need to specify audio vs audio and visual telemedicine application and should articulate heightened privacy and security risks associated with the transmission of health information via audio and visual technology. The patient should be able to decline a telemedicine consultation for any reason including fear of breach in security, discomfort with the process or simply a lack of familiarity with the process. Consent should be documented in the record.

Medical Director 0n-scene; remote specialist still remote: If the EMS Medical Director provides care in the prehospital setting (“the field”), clearly defined roles and responsibilities should be established between the Medical Director and the remote consulting telemedicine specialist. The EMS agency’s Medical Director should have his/her role clearly defined to assure that a contracted telemedicine provider’s orders do not supersede the Medical Directors oversight. This should apply to on-scene and off-scene scenarios

Non-Transport of patients: Telemedicine can be applied to low-risk situations where the patient may be treated and released for non-urgent situations such as minor wounds or low-acuity respiratory complaints (mild asthma exacerbations) and even minor allergic reactions. In such situations a prescription may even be offered and provided (e.g. prescription refill for a metered dose inhaler or nebulizer medications for the asthmatic patient who called 911 because he/she ran out). Another appropriate application would be when there is consideration of transport to an alternative destination other than an emergency department when 911 was activated for a non-urgent situation (e.g. minor laceration). Care should be taken to understand and comply with applicable remote prescribing requirements, including establishing an appropriate patient relationship as defined under state law prior to prescribing.

Patient Expires on-scene and TeleMedicine in progress: EMS Systems utilizing telemedicine in the field should have established protocols and guidelines clearly defining the actions and steps the EMS crew should take in the event that the patient expires in the field while EMS is using telemedicine services.

TeleMedicine Equipment Inoperable or Stolen From EMS Vehicle: In the event that the telemedicine equipment is inoperable (regardless of reason) and/or stolen, EMS crews should continue to provide the appropriate level of care and always be ready to address a situation where telemedicine becomes unavailable. Depending on the EMS system and the nature of the telemedicine consult, it may be appropriate for the remote specialist to provide guidance/recommendations to the EMS crew via telephone in some circumstances.

Technology ownership (e.g. boat, ambulance, plane, helicopter, ski sled, ): There are several non-technical questions to answer regarding the use of telemedicine technology in EMS. Examples include: Who is providing what technology to whom and at what price? Who is paying for the software and/or hardware? Consider having legal/compliance review the details of how the equipment is being provided to the remote telemedicine specialist. Due to the potential for possible fraud and abuse, details such as these should be vetted, and recommendations provided.

Technology Maintenance: For telemedicine technology maintenance and support, it must be clearly defined which organization is responsible for routine and emergency service. Details such as service level agreement should be clearly defined and documented. In addition, hardware warranty information should be included in any contractual arrangement.

HIPAA / HIITECH: Any technology used with an EMS telemedicine system must ensure the security of personal health information and protected health information. Failure to ensure this can have multiple implications such as contract breach, patient dissatisfaction, remote telemedicine dissatisfaction, and potential penalties and litigation. Ensuring issues such as security is key in combating the potential for security issues such as cyber attacks, connection breeches, and session intrusion. Cyber and privacy liability insurance coverage may also help to mitigate risk associated with an unauthorized use or disclosure of health information.

Software: The software used in the EMS system’s telemedicine program should include HIPAA and HIITECH safeguards, and the software must be maintained. The ideal situation is for the software to be “evergreen”, or automatically updated. Cyber security factors must also be anticipated, reviewed, and addressed. Depending on the telemedicine environment (urban, suburban, rural, or remote), the frequency and file size of updates may need to be considered as internet access may be slow or non-existent.

Connectivity: Ground EMS involves responding to urban, rural, and suburban environments. EMS telemedicine connectivity, such as WiFi, cellular, and satellite, must all be considered.

Who Is Paying For What: When providing telemedicine services in the prehospital setting, it is important to be aware of which agency is purchasing or providing which equipment to which healthcare provider. Many healthcare systems, including hospitals and EMS systems, have guidelines regarding participating in arrangements that may bestow value on a potential referral source and safeguards in place to avoid arrangement that may generate remuneration in favor of a referral source based upon the volume or value of services furnished in connection with those referrals. When reviewing the overall structure and relationship of the EMS telemedicine model, it is important to have legal/compliance involved in the process.

Referral Patterns: In many cases EMS systems and the EMS crews have pre-determined protocols and policies regarding where patients are referred to. If telemedicine is being used in the field, do the hub hospital (medical control), potential spoke sites (referral facilities), and EMS crews (functioning under hub physician license) with telemedicine in-play have established rules / guidelines / policies specific to patient referrals?

Vehicle issues: A vehicle is transporting a patient who is receiving active care via telemedicine. If an issue arises with the transport vehicle, all involved parties (e.g. telemedicine provider, EMS crew, receiving facility) should have a working knowledge of what to expect and do if and when the patient arrives? If the patient needs to be transferred to another vehicle that does not have telemedicine equipment, procedures and protocols should be in place to ensure the continuity of care despite telemedicine no longer being available.

Technical issues in the field: Potential issues with hardware, software, and connectivity must be anticipated in advance and included in any contracts and written protocols. It is possible to encounter connection issues during an audio/video consultation. What is the technology solution? Examples of solutions include removing video to support audio only or to switch to cellular (if possible) audio only.

Payor Reimbursement: As with any healthcare service, a review of payer reimbursement must be performed. TeleMedicine in EMS is no exception. There are a minimum of 2 payments that will occur with telemedicine and EMS. First, the remote specialist will need to be paid. Payment structure should be determined before the remote telemedicine provider begins providing services. Second, if the EMS crew is a paid crew, they will receive payment (e.g. hourly rate) for the services they are providing. Healthcare provider payments will need to be determined before services are rendered. In addition, if a payor (e.g. insurance company) is paying a healthcare provider, that same provider should not be receiving additional compensation for services provided.

Consulting provider referral incentive: When creating the EMS telemedicine service line, the relationships of all involved stakeholders must be clearly defined. In addition, potential and/or existing patient referrals should be thoroughly reviewed. Referral criteria and policy can be addressed in contracts. It is recommended that the remote telemedicine clinician’s services be reviewed. Based on review of the remote telemedicine provider’s affiliations and peer relationships, the potential for referral incentives should be minimized wherever possible. Review by legal and compliance can be helpful with this.

Provider Scope of Responsibility. Prior to going “live” with an EMS TeleMedicine program, the following scenario must be reviewed and options / policies clearly documented and operationalized for the EMS crews. If an EMS crew is transporting a patient to a healthcare facility while a telemedicine session is in progress and the patient suddenly deteriorates, what are the expectations of the (1) remote telemedicine provider, (2) EMS crew, (3) receiving facility. While the solution may appear to be obvious, the details should be reviewed by all stakeholders in advance. Recall that EMS crews provide healthcare services in the field, often under the EMS system’s medical director’s license. It may be that the remote telemedicine provider is a licensed physician that is not affiliated with the EMS agency or receiving hospital. In cases such as this there could be 2, and possibly even more, licensed physicians involved including the remote telemedicine physician that may be guiding care during EMS transport, the EMS system’s medical director, and potentially even the physician in the receiving hospital. There could also be more than 1 remote specialist involved in the same telemedicine session (e.g. multi-presence with more than 1 specialty).

Marketing: While it is great to inform the local community that the local EMS agency has telemedicine services, how the services are “marketed” may require legal and compliance review. The partnership of affiliated and non-affiliated facilities and/or EMS vehicles and the addition of telemedicine services may need to be “branded” in a specific way.

Technology for free: A healthcare system or hospital may seek to provide technology at no cost to EMS crews and remote telemedicine providers. A healthcare system providing telemedicine technology to remote consulting providers and/or EMS crews can be perceived as an incentive to shift the patient to the donating organization. The “tech for free” model should be reviewed by legal / compliance.

Social Media: What happens when a bystander captures the telemedicine video display on the vehicle’s telemedicine device and then shares the screen capture on social media? Is this a potential HIPAA violation? Was protected health information or personal health information shared?

TeleMedicine Documentation: Similar to any healthcare interaction, there should be a written document that accompanies the patient’s chart. There should be established details regarding documentation including submission due-dates or turn-around-times, as well as acceptable formats such as care continuity documents (CCD) and PDF details. After care instructions can be generated from telemedicine software. These may be prefabricated for the most common complaints and supplemented with personal notes. Such instructions can be embedded within the EMS medical record as well as sent to the patient via email or text if arranged in advance.

Contract breach: Similar to other healthcare services, telemedicine in EMS will involve several contracts. Items such as clinical service levels, pricing, technology standards, escalation policies, and factors such as breach and mediation details can be included.

Conclusion: Telemedicine offers some exciting opportunities to bring expertise not previously available to EMS providers. Similar to traditional methods of delivering healthcare in the prehospital setting, it is highly recommended that established protocols and guidelines be developed for telemedicine services. Having key stakeholder involvement early in the process will assist the program in avoiding potential pitfalls while ensuring the optimal delivery of high-quality care in a cost-effective manner.

References

Federal Interagency Committee on Emergency Medical Services (2021). Telemedicine Framework for EMS and 911 Organizations.

Simon, L., Shan, J., Adina S. et al. (2020) The Journal of Emergency Medical Services. Paramedics’ Perspectives on Telemedicine in the Ambulance: A Survey Study. Retrieved from https://www.jems.com/exclusives/perspectives-on-telemedicine/

TRACIE: Healthcare Emergency Preparedness Information Gateway. (2017) Retrieved from https://files.asprtracie.hhs.gov/documents/aspr-tracie-ta-paramedicine-and-telemedicine-resources-022317-508.pdf

New York Department of Health. (2020) NYS Medicaid COVID-19 Telehealth/Telephonic FAQ. Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Use of Telehealth including Telephonic Services During the COVID-19 State of Emergency. Retrieved from https://health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/covid19/docs/faqs.pdf

Pulsara (2021). Clarkson, K. Does HIPAA Allow Hospitals To Share Patient Data With EMS? Retrieved from https://www.pulsara.com/blog/does-hipaa-allow-hospitals-to-share-patient-data-with-ems

Elizabeth Lazzara, E., Benishek, L. (2017) Human Factors and Ergonomics of Prehospital Emergency Care: Chapter 10 Exploring Telemedicine in Emergency Medical Services: Guidance in Implementation for Practitioners. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316300531_Chapter_10_Exploring_Telemedicine_in_Emergency_Medical_Services_Guidance_in_Implementation_for_Practitioners

Kaiser Family Foundation (2021). Women’s Health Policy. Opportunities and Barriers for Telemedicine in the U.S. During the COVID-19 Emergency and Beyond. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/opportunities-and-barriers-for-telemedicine-in-the-u-s-during-the-covid-19-emergency-and-beyond/

Columbia Southern University. The Link. (2019) Why Telemedicine is Growing in EMS. Retrieved from https://www.columbiasouthern.edu/blog/january-2019/ems-telemedicine/

Yesul, K., Groombridge,C., Romero, L., Clare, S., Fitzgerald, M. (2020) Journal of Medical Internet Research. Decision Support Capabilities of Telemedicine in Emergency Prehospital Care: Systematic Review. Retrieved from https://www.jmir.org/2020/12/e18959/

Author Bios

Paul Murphy

Paul Murphy, MS, MA, Paramedic, has been involved in healthcare for 20+ years. He initially worked in clinical roles, including the Denver Paramedics, and then transitioned to start-up and established healthcare companies. His virtual care experience includes working for a leading virtual care vendor and a large healthcare system with a mature virtual care / telemedicine program. He has published articles in a variety of healthcare journals.

Dr. Christopher Colwell

Christopher Colwell, MD, FACEP, has been the Chief of Emergency Medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center since 2016. Dr. Colwell received his bachelor of science degree from University of Michigan and his medical doctorate from Dartmouth Medical School. He completed residency training in emergency medicine at Denver Health where he served as chief resident. He is a fellow of the American College of Emergency Physicians. Dr. Colwell was formerly chief of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Denver Health and professor and executive vice chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at University of Colorado School of Medicine. He is a leader in Emergency Medical Services (EMS), serving for over a decade as medical director for the Denver Paramedic Division, medical director for the Denver Fire Department, and EMS fellowship director. He was the senior associate EM residency director at Denver Health and is an ABEM oral examiner. He served on the Board of Directors for Colorado ACEP, and serves on a number of state and national EMS and trauma committees. He has been honored with multiple awards for his contributions to EMS and trauma care, and has published more than 100 manuscripts or book chapters in the areas of prehospital, emergency and trauma care.

Dr. Gilbert Pineda

Dr. Gilbert Pineda is a board-certified specialist in emergency medicine who comes to St. Vincent from physician-owned and operated CarePoint Health. He practices clinical emergency medicine and has taught many prehospital providers and other physicians during his more than 30-year academic and clinical career.

Dr. Pineda grew up in Huntington Beach, California, earned his undergraduate degree in psychobiology from Occidental College and attended medical school at the University of California Irvine. Residency training took him to Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center (LAC+USC), where he remained as clinical faculty for an additional seven years. He was a clinical instructor of emergency medicine at Denver Health Medical Center for 14 years and has lectured nationally and locally on emergency medicine and prehospital medicine topics.

What drives his patient care philosophy? “I believe in practicing and preaching compassionate clinical medicine within a world of medical technology,” says Dr. Pineda. “It’s one reason, of many, why I’m attracted to the practice at St. Vincent Health.”

Dr. Pineda is also board-certified in the subspecialty of emergency medical services (EMS). He has been the medical director of the Community College of Aurora’s EMS program since its inception in 2000. He was the medical director for the City of Aurora for over a decade and provided EMS medical direction for many communities in eastern Colorado as well.

When Dr. Pineda isn’t treating patients, he’s likely out enjoying snow sports or a vigorous hike. “I like to relax after a hike with a good India Pale Ale,” he says with a laugh, and adds, “My family keeps me down-to-earth most of the time.”

Clay Wortham

Clay Wortham, Founder and Principal Attorney at Wortham LLP, is a business-focused healthcare transactional and regulatory lawyer with sophisticated experience structuring complex healthcare transactions. With a background of service in large law firms and as inhouse counsel with one of the Nation’s largest retailers, Clay is ideally suited to counsel healthcare organizations and those who do business with them on how best to achieve their objectives while mitigating the legal risks of operating in the heavily regulated healthcare environment. Clay’s current representations include diligence and guidance for health system acquisitions and joint ventures, negotiating telemedicine and telehealth provider arrangements and structuring pharmaceutical distribution and supply networks. Clay is a go-to resource for businesses seeking to comply with healthcare regulatory requirements, including Federal and state health information privacy and security laws, and fraud and abuse laws such as the Federal Anti-Kickback Statute, Stark Law and False Claims Act. Clay also helps clients navigate commercial payor and Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement issues. Clay is uniquely experienced with respect to pharmaceutical distribution and pharmacy regulatory matters, including state Board of Pharmacy requirements and DEA controlled substance compliance. Prior to founding Wortham LLP, Clay served as a member of the Dentons Health Law Group in Chicago and as senior corporate counsel for Walgreen Co. in Deerfield, Illinois.

Scott Nelson

Scott Nelson has been in EMS for more than 3 decades, starting as an EMT in Denver, Colorado in 1989 and certifying as a Paramedic in 1992. Scott has worked as a 911 Paramedic and manager in a private ambulance company prior to working as a remote site Paramedic in Alaska. He is currently the EMS Program Director at Texas Southmost College in Brownsville, Texas.

The Editorial Team at Healthcare Business Today is made up of skilled healthcare writers and experts, led by our managing editor, Daniel Casciato, who has over 25 years of experience in healthcare writing. Since 1998, we have produced compelling and informative content for numerous publications, establishing ourselves as a trusted resource for health and wellness information. We offer readers access to fresh health, medicine, science, and technology developments and the latest in patient news, emphasizing how these developments affect our lives.